Leadership Notes #59

Interview: Terry Szuplat

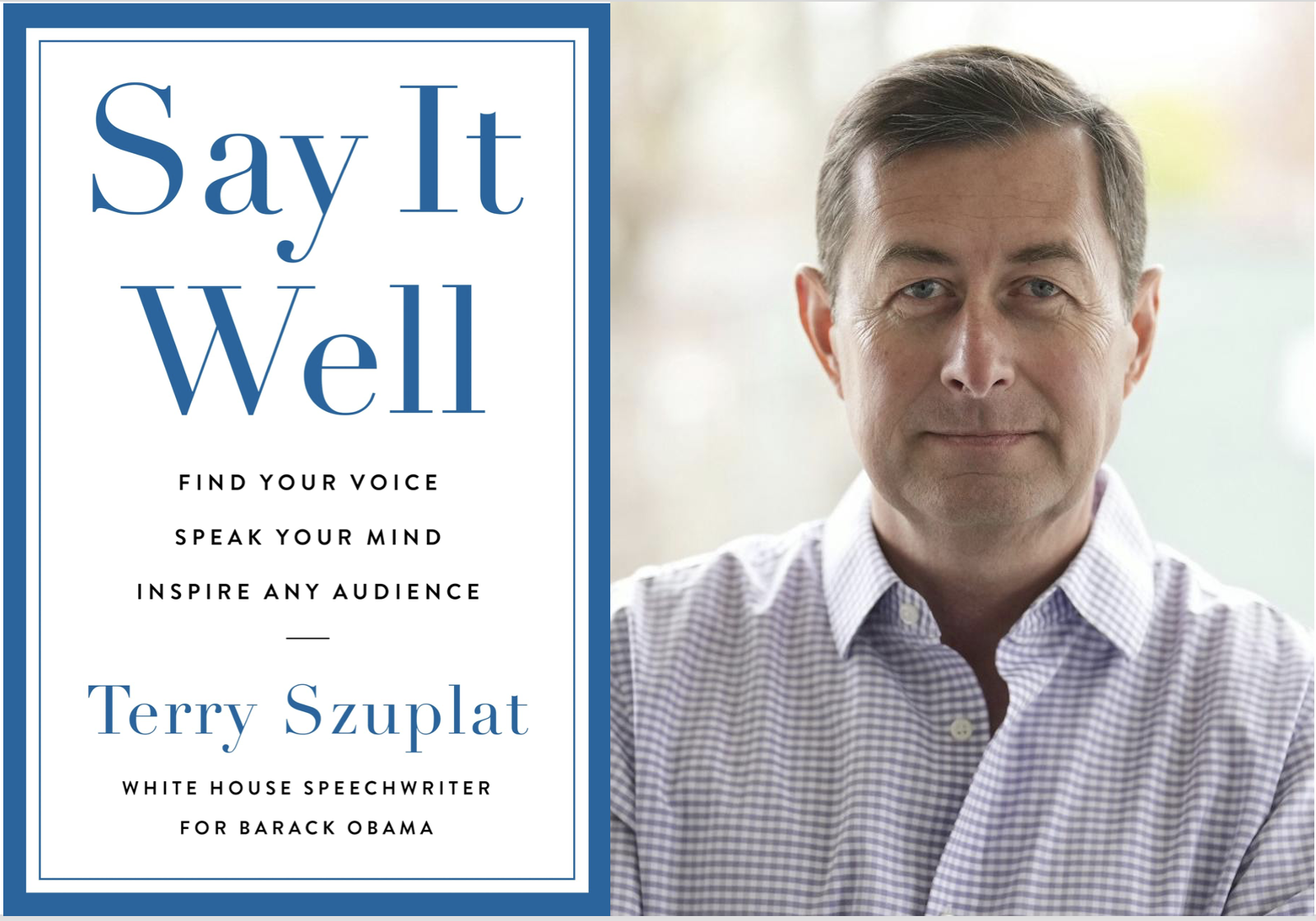

Terry Szuplat is an award-winning author, speaker, and trainer whose keynote presentations and workshops empower audiences with the communications skills he learned as one of President Barack Obama’s longest-serving White House speechwriters — lessons he shares in the national bestseller Say It Well: Find Your Voice, Speak Your Mind, Inspire Any Audience.

An Obama speechwriter from 2009 to 2017, Terry helped craft nearly 500 speeches on global security, international economics, U.S. foreign and defense policy, entrepreneurship, development, and human rights. As a Special Assistant to the President, and Senior Director of Speechwriting at the National Security Council staff, he joined President Obama on visits to more than 40 countries.

While serving as the deputy director of the White House Speechwriting Office in the West Wing during President Obama’s second term, Terry helped oversee and edit the work of a team of speechwriters, assisted with State of the Union addresses, and produced innovative content to reach new audiences through social media.

Today, Terry harnesses his nearly 30 years of experience to help leaders in politics, business, NGOs, philanthropy, and entertainment inspire audiences around the world. As a keynote speaker and trainer, he takes audiences on a journey behind the scenes of the White House and shares the skills than can help anyone become a better speaker, communicator, and leader. He also teaches political speechwriting as an Adjunct Professor at American University’s School of Public Affairs where he was selected for the Outstanding Teaching in an Adjunct Appointment Award in Spring 2025.

Learn more about Terry’s professional work here.

A condensed transcript of Terry Szuplat’s appearance at PGLF at CIED Georgetown’s Virtual Author Series

Potolicchio: Terry, you mentioned in Say It Well that you should start off a speech by saying “Hello!” for instant connection. Why should we say hello immediately when we meet an audience?

Szuplat: One of my favorite videos of all time from those eight years in the White House with President Obama, and anyone can go on Google and find this, is a two-minute sequence montage of him saying hello to people all over the world in their native language. He did this a lot, of course, as a candidate, but then, as we sent him all over the world and I joined him on trips to more than 40 countries. This is something that we worked really hard on. What better sign of respect is there than to actually greet someone in their own language? Something really simple yet powerful happens when we say “Hello!” We usually smile. So many speakers forget to smile when they're talking to their audience. Saying hello, greeting them, smiling, so many people don't do it. It's one of the easiest ways to forge an emotional connection with your audience, which is what great public speaking communication is all about. Yes, the information is important, the message is important, but it's also about the emotional connection with your audience.

Potolicchio: You're going to get a quiz here at Georgetown University. May 11th, 1995, what does that date signify in the life of Terry Szuplat?

Szuplat: I was an intern at the White House speechwriting office. The president was Bill Clinton at the time. I was an intern, so most of the time I was grabbing coffee and doing research, but I think that was the day that President Clinton was visiting a newly independent Ukraine. I was assigned the glorious and prestigious task of writing talking points for the president to speak to our U.S. Embassy staff in Kyiv—in the gymnasium. I was 22 years old, and I got a chance to help write some words for the President of the United States as a Ukrainian-American. It was a special privilege, and it put the bug in me. Fourteen years later, I came back as a presidential foreign policy speechwriter myself.

Potolicchio: I want you to tell me who wrote these words about you: “Terry Szuplat, the deputy director of speechwriting, an affable old man of the group at 42, sat in the windowless office even closer to the underworld than mine with a thick shock of hickory hair parted on the left and lids that drooped over the outer edges of his blue eyes until they met the creases that betrayed years of laughter."

Szuplat: It's Cody Keenan, our chief speechwriter in the second term. For those of you who want just a beautiful inside account of what it's like to work in the White House, write speeches with President Obama, Cody wrote a beautiful book called “Grace.”.Here I am, promoting somebody else's book! But it's a beautiful book. It's about the 10 days following the shootings in Charleston, South Carolina, culminating in that amazing speech where President Obama sang Amazing Grace. Cody's book captures those 10 days, takes you behind the scenes, including the guy who sat next to him with the droopy eyelids for four years.

Potolicchio: We're going to have a Netflix movie about the Obama presidency, you're the main character and you're going to tell us what that opening scene of your movie is. Here’s Cody again writing about you. “Terry served as my most important advisor and sounding board over two terms in the White House. He probably drafted more remarks on foreign policy and national security than any other presidential speechwriter in history. Even though, like Obama, he was out the door every evening at 6:30 sharp to have dinner with his wife and two children at their home before reopening his laptop to work later at night”. What's the opening scene of a Terry Szuplat biopic and why?

Szuplat: It's November 2008, Barack Obama has just been elected the first black president in American history. I had volunteered on the campaign and got to know his speechwriters a little bit. They reached out and asked: “Would you like to apply to be a speechwriter for President Barack Obama?” The call that every speechwriter dreams of getting. The answer is yes, but then, they say, "All right, we have a number of candidates who would love this job of a lifetime. Here's a speechwriting test.” They gave me a prompt, a scenario, a fictitious speech. They said, "You have seven days to write this speech." I knew that if it went well, I could perhaps get the job and if it didn't go well, I'd miss the job of a lifetime. I cleared my schedule for the week. My wife was amazing. She just took the kids and I barricaded myself in my home office and went to town. For the following seven days, I would write the speech that no one would ever speak, no one would ever give or deliver, and no one would ever hear, but it would be the speech that would decide whether or not I got this incredible opportunity.

Potolicchio: I have a curiosity, Terry. When you read Cody's book, he talks about the toll that it took on him and his health. This is a very difficult job and yet you made it look easy. This is Cody writing about you: “Speech writing was never easy, but Terry made it seem more effortless than most. He'd been writing speeches since the 90s when he was a young scribe at the Pentagon before becoming the Secretary of Defense's chief wordsmith at the ripe old age of 25.” Now, it's not just your stamina, it's the pressure. A lot of us have had writer's block, that blinking cursor. But as a president’s wordsmith? And specifically to President Obama. I don't know if this actually was said or if it's apocryphal, but he said he was a better speechwriter than even his speechwriters. Is that true or false, by the way?

Szuplat: That's what was reported.

Potolicchio: Your prose from Say It Well: “Obama remained seated with his lunch, another salad, I think, once again, half eaten. I stood there leaning over his shoulder as he calmly walked us through his changes. I was stunned. I thought he'd been playing tourist all morning. Turns out he'd been rethinking his remarks the whole time and rewriting during breaks. And he didn't simply have edits. He'd restructured much of the draft, circling sentences and moving them to different paragraphs, marking entire paragraphs and moving them to other pages, reshaping the back half of the speech. The last hour was a heart-stopping blur. I still didn't know how we made all these changes. At one point, with the audience already in their seats, Obama was waiting backstage, catastrophe struck. I lost my connection to the internet. The speech was trapped on my laptop.” Can you give us a regimen or some type of methodology for how we can be calmer, as cool as the other side of the pillow, when we have high-stakes communication and writing?

Szuplat: That was in Athens, Greece, right after the 2016 election. The president had been planning to give a big speech in Greece, about the birthplace of democracy, the assumption was that Hillary Clinton was going to win, democracy had prevailed and it was going to be a big celebration of democracy. I'd written that speech and then the president, as he traveled around Europe and Greece, was reworking the speech to make it more suitable for the moment. There were so many moments like that. One of the things I learned through those eight years was that, and I don't know if this is a Jedi mind trick, but if I panicked, I froze. I could not do my job. I had to think, my fingers had to move, I had to type out words. If I froze or I lost my cool, I couldn't do that job. And if I couldn't do that job, I would lose that job and I love that job. I wanted nothing more than to keep that job and to keep doing it for as long as I could, as long as my family would allow.

It was very much just breathing deeply and trying to center myself in that moment and realize that for me to serve this person, for me to get this job done, I had to stay calm. It was the only way. Every minute that I froze, every minute that I panicked was a minute I wasn't writing or thinking. That's something that I had to learn over time. I will say there was one time, I remember it very distinctly, where I think I did kind of freeze up a little bit. One of my colleagues could see it, could sense it, and sat down and kind of just typed it out for me. I wasn't perfect, I still had my moments. But I think more often than not, that was what I tried to tell myself, and I think we all know this: When we panic, we make bad decisions. When we panic, we can't do our jobs. That's an emotional reaction to a situation. I tried as best I could to just stay calm.

Potolicchio: But how do you last eight years? You're going to 40 countries. You're constantly under this grind. You know your words are going to be, one of your colleagues joked with you when you were writing a speech in India, “listened to by only a billion Indians.” How did you do this over the long haul?

Szuplat: I was working on a speech for the president to give to the Indian parliament and it was going fine. I'd done it many times, worked as a speechwriter for years and this NSC staffer said: "Don't worry! Only a billion Indians will hear it.” At that point, I completely froze up. This whole thing became much bigger and I really struggled to write that speech.

I loved [the job] and I was so grateful to be there; it was something I had worked for four years. I had always dreamed of being a presidential speechwriter and to be a speechwriter for Barack Obama, of all people. I wanted to do it, I loved it. When it worked well, it was something beautiful to watch. A lot of speechwriters can't bear to be in the room when the speaker delivers the speech. I love being in the room because I spent weeks thinking about how to create a good experience between that speaker and the audience.

I would try to sit in the front or off to the side and I wouldn't watch the speaker, President Obama. I would watch the audience, I wanted to see their faces. Were they laughing and smiling when they should have been? Were they thinking, sitting quietly and listening when he wanted them to be? Were they leaning in? I wanted to see if they were having that experience that we wanted them to have and to take away what we wanted to have. I loved it. It was brutal, the hours, the travel was brutal, but then, you go and sit and have a moment like that with several thousand or hundreds of millions of people watching this thing and have a positive experience. Those experiences sustain you not just for days, but for weeks and months. We'd get that every few days, so it was a constant replenishment and a reminder of why I loved what I do.

One of my students at American University asked me recently, “Do you have to love your job?” I don't know if everyone would agree, but I actually don't think you have to love your job. I think a lot of people probably don't love their job. You have to like it on some level, but my God, if you actually love what you do and draw fulfillment from it, then it doesn't always feel like work.

Potolicchio: Terry, you mentioned atmospherics, thinking about the audience, the surroundings, not just your words, when you're writing these speeches and when we communicate. 13 years ago, I was teaching a class at Georgetown on presidential rhetoric in the first semester of the summer term, so in June. It was right around the summer solstice when I got an email and they asked if I wanted to take my presidential rhetoric class to have front row seats to listen to President Obama give a speech on climate change. I thought it was going to be in Gaston Hall, which is this incredible place on campus, ornate, just gorgeous aesthetically, but they told me that it was going to be given outside. In 95 degree Washington humidity. (Potolicchio plays a video of Obama addressing Georgetown students on the outdoor presidential steps “First announcement today is that you should all take off your jackets. I'm gonna do the same. We're good.” )

The rest of the speech, he is just sweating like there is no tomorrow. I think he broke the Guinness World Record for most dabs of sweat off the forehead. So obviously, the world's heating up, you're listening to my speech, we've got to make some policy changes because as you can see I am physically burning. How important are atmospherics for our own day-to-day communication when we have a difficult conversation with one of our family members? And how much did you think about them as you're writing these words for the president?

Szuplat: This is something that we thought about all the time. One of the best predictors of success is actually not what you say when you speak, it's all the work that goes into your preparation. Because you can make big strategic choices, and you can make the wrong choice.

Is this a big event where people are expecting a big speech? Is it a formal event? Should we all be wearing suits or should we take them off? Before you ever say a word as a speaker, all these atmospherics are affecting the mood and the spirit of your audience. Is it the first thing in the morning? Is it late at night? No one wants to hear a big policy speech at eight o'clock at night. Is everyone standing around holding drinks? Nobody wants a big, long speech when you're doing that. Have they come for a big policy keynote? Nobody wants short remarks that are light and unprepared, where you think you're going to wing it.

In my book, I have a list of all the different things you should be asking yourself, as a speaker, before you ever write down a single word. Unless you're president of the United States with a podium, it's really hard to do a big speech outside most times. The tolerance of the audience for something big and sweeping is pretty narrow.

In my role at the White House or elsewhere, people would hand me a speech or my fellow speech writers would say, "Hey, I've written this speech." It's a beautiful speech, five pages, 20 minutes long. I said, “Where is this happening? Is it outside?” If it's outside and everyone's standing, no one's going to be in the mood for a 20-minute speech. The big idea to remember is, yes, the information is important, you've got to get your message right, but that only gets you so far. If you want to go from good to great, you've got to think of this for what it is: a performance. You are a human being in front of other human beings. You're there to establish an emotional connection. All of this plays into it.

Potolicchio: If we were going to interview President Obama and ask him which speech would be considered the Terry signature, the most impressive speech that you wrote for him, it has to be the remarks after the Boston bombing, right? Do you think that would be considered the speech that he would say, “this is the one that might be the most memorable that Terry scripted”?

Szuplat: I don't know what he'd say. We had a whole team of speech writers, but I would say that's one that I was very proud to work on. I was born in Boston, grew up in Massachusetts, and spent so much of my life in and around Boston. When the Boston Marathon bombing happened, we found out he was going to go up and speak at the memorial. I asked my team if I could take the lead on that. The reason was that I knew that so many of my family and friends were hurting. I knew that this would be a moment that perhaps could help in the long healing process, perhaps could show some solidarity from the country, and give them some comfort and strength to get through this awful moment. Interestingly, at the end of the administration, the White House asked the entire speech-writing team, “What was your favorite speech to work on?” We each gave our answer. Medium did a post on it. What's interesting is that they're actually not the most famous Obama speeches, but they are ones that meant a great deal to us.

I think this is true for all of you watching, too. You'll be better as a speaker and as a communicator when you are speaking about the things that you care about, that you truly believe in. You should talk about what means the most to you and what means the most to me. It sounds obvious, but it's not. A lot of speakers just go out there and say, “I'm going to talk about X, Y, and Z.” You will be at your best when you are speaking from your heart to their hearts. That means thinking deeply about who you are, what you believe, what you care about, and what your values are. Think about the leaders who have inspired you, the speakers who've inspired you. They're always doing that.

Potolicchio: I want to read some language from this speech and then get you to talk about the concept of Uncle Dan. “Our prayers are with the Richard family of Dorchester -- to Denise and their young daughter, Jane, as they fight to recover. And our hearts are broken for 8-year-old Martin -- with his big smile and bright eyes. His last hours were as perfect as an 8-year-old boy could hope for -- with his family, eating ice cream at a sporting event. And we’re left with two enduring images of this little boy -- forever smiling for his beloved Bruins, and forever expressing a wish he made on a blue poster board: “No more hurting people. Peace.” No more hurting people. Peace.

Our prayers are with the injured -— so many wounded, some gravely. From their beds, some are surely watching us gather here today. And if you are, know this: As you begin this long journey of recovery, your city is with you. Your commonwealth is with you. Your country is with you. We will all be with you as you learn to stand and walk and, yes, run again. Of that I have no doubt. You will run again. You will run again.

Because that’s what the people of Boston are made of. Your resolve is the greatest rebuke to whoever committed this heinous act. If they sought to intimidate us, to terrorize us, to shake us from those values that Deval described, the values that make us who we are, as Americans -- well, it should be pretty clear by now that they picked the wrong city to do it. Not here in Boston. Not here in Boston.” Uncle Dan. How did Uncle Dan help you write this speech? What is something that we can take away from it in our own lives?

Szuplat: One of the hardest things that a lot of us face as speakers, as communicators, is how we connect with so many people in the audience. They're so different, from all sorts of backgrounds. It's hard to connect with that many people. When you write, just imagine one person who will be in that audience, ideally one person you know, and write that speech for them. You will find that you write a much more powerful, emotional, personal, evocative speech. If you're trying to write a speech that's trying to be everything to everybody, it gets watered down.

In this particular case, as I was working on that speech, I was thinking of all my family and friends back home, including my uncle Dan, my mother's brother. I thought of him because he was sort of Boston-born and bred. He's everything you love and don't love about Boston. And he happened to be a very conservative guy who didn't care for Obama. Our Thanksgivings could get a little dicey sometimes. I was thinking, what could Barack Obama in that moment say to someone like my uncle to kind of cut through all these partisan divides and connect with him on an emotional level? Part of what you read and so much of the rest of the speech was very much what one White House staffer later called “a kind of love letter to Boston.” It was a celebration of a city and a spirit and a defiance that anyone should be able to feel a connection to, regardless of politics. And so that's what it was.

Later on the day of the speech, I noticed I got a voicemail and it was from my uncle. As I was writing it, I'd imagined him watching the speech in a bar with his buddies, because that's where he spent a lot of his time. And I could tell from the voicemail, from all the noise in the background, that he was watching in a bar with his buddies. In his thick Boston accent, he just said something like, “Terry, I just want you to know we all watched the speech. It was a very fine speech. The president did an excellent job, a fine job.” And he hung up. But it was a great reminder that as communicators, as speakers, we're at our best when we just try to often write just for one person. Last week, I had to give a eulogy for my other uncle, his brother, and I wrote it for his wife, his children, and my mother more than anybody else. There were dozens and dozens of people there. We all wanted it to work. But more than anything, I wanted it to be a gift for his wife, his daughters, and his sister, and from that, everybody else. Write for one person, imagine one person. Who is your Uncle Dan when you write and speak?

Potolicchio: My last question is about learning. You write in your book about a speech after another tragedy. One of your colleagues was able to chase down a detail. A child was born on 9/11, and he found a book of children who were born on 9/11, and found out that this child loved to jump into rain puddles. When Obama ended his speech, Obama says, “If there are rain puddles in heaven, Christina is jumping in them today.” Can you talk about how learning improves our writing? Getting those details and finding a way to learn about the world and how that can take us to the next level as we connect with audiences or we write for someone like Uncle Dan.

Szuplat: Something I really stress when I teach is that if you want to be a great speaker, a great communicator, you have to think of yourself as a great storyteller. We actually all know how to tell stories. We're at family gatherings and we tell a story about something that happened that made us happy or sad. We don't say, “She cared about her family and her work.” You tell a story, give examples, and vivid pictures. The little girl skipping the rain puddles, the little boy from Boston holding his sign, eating ice cream, those are images, mental pictures. Great communicators create these moments. It's that basic lesson that we learn in grade school: show, don't tell. Don't tell me you're happy, show me you're happy, give me an example. When we grow up, we get into the professional world, we go to school, we're taught to back up our arguments with data, statistics, numbers, and charts, and we forget how to be storytellers. We're great storytellers in our own lives, but then in a professional world, we stop.

A big theme of the book is how to become a better storyteller, how to draw on those experiences from your own life, not in a narcissistic way. No one wants to listen to a narcissist, but to be vulnerable and open and share things from your experiences because that's how we connect with each other. That's what people remember. When they remember, they're more likely to do what you are asking them to do again. We shouldn't just be out there talking to talk, although too many people do it, especially politicians. They talk to hear themselves talk. We should speak and stand up and give speeches and presentations because we want our audience to do something different, to believe something different, to leave the room, go out, act and believe differently. The best way to do it is to build trust and credibility through human connection and human storytelling.

Monoses: In light of recent world events, when you are writing words that may influence war, justice, national healing, and peace, how do you personally carry that moral responsibility?

Szuplat: Every time we wrote for the president, in my case, President Obama, it was never lost on us that lots of people would be watching and the words mattered. Obviously, we're seeing that every day now, the consequence of words that are both thought out and not thought out. We put great thought into every single sentence, every single word. I know people always feel like all politicians lie and they're always in it for themselves, and their staff don't care. They're the elites. I can't speak for other people. I can only speak for myself and my team. We were honored to be there, to have that opportunity. I'll give you a story to show you an example. President Obama gave a speech on civil society and standing up for human rights and democracy one time. The speech was given, went well, and we were on to other things. A few weeks later, someone from the White House came to me from our National Security Council and said, “I just got a message from a human rights advocate in Egypt.” This person was on the ground every day, risking their lives to build the kind of future and country that they wanted. That advocate had printed out and carried President Obama's speech in their coat pocket as a reminder of why they do what they do every day. I couldn't believe it. Those words gave this person strength, it gave them hope, and it gave them sustenance to continue their work. Knowing that these words mattered helped us to bear that responsibility. It's a good reminder to all of us, too; our words go out, and they have an effect. I would hope that we would choose to use words that bring people together, not divide people, that lift people up, not tear people down. That builds compassion and does not just feed the cycle of cruelty that we're in.

All of us have the opportunity to do that when we're speaking at a dinner table with our family, at a cookout with our neighbors, at a community meeting, or when we're posting online. We have a choice on how we're going to communicate and be present in the world. That's a big theme of the book to try to urge people to embrace that responsibility in our own lives.

Guadalupe Ramirez: I would love to hear your thoughts on AI and speech writing. Are you using it? If you're using it, how do you still keep that authenticity?

Szuplat: I started writing this book in 2020-2021 and I thought that AI was going to change things, so I thought I needed to reassess how I wrote this book. Throughout the book, there are these little asides about when you should beware of a bot and when you might ask a bot for some help. I'm not one of these people who said it's all terrible and it's all good, I have mixed feelings about it. This may change years from now, but as of today, I have two basic rules. As a research tool, as a thought partner, as an editor, AI is amazing. It can save you hours of work. It gets drunk and hallucinates, but it's a remarkable tool. It can come up with an outline or can help me explore topics and themes, so as a thought partner, it is great. When the moment comes to actually write down the words that you, a human being, are going to speak to an audience of human beings, I beg you, don't use a bot for that! That is not why you're there. If you're going to do that, just send them a memo, an email. You've been invited to speak to a group of human beings because they want human connection. I think this is more important as AI takes over more of our lives.

I had someone tell me once, “I used AI to write a eulogy.” I was thinking, “My God, are you kidding me? That's not what those people needed in that moment.” You're speaking to an all-hands meeting at work, they need to hear from you, a leader of their organization.

So it's an incredible tool. But our voice, how we speak, our story, our experiences, our lives are one of the most powerful tools we have as leaders, and AI doesn't know that. They're going to give you something generic. Maybe five years from now, as it learns more about you, maybe it'll learn about your voice. But as of today, I beg people, please don't use AI when you are a human trying to connect with other human beings.

Potolicchio: What about routine? When you go up to give a speech, you have some nerves. I don't want to ruin the punchline to your book, but the opening scene has to do with some of the nerves that you may have had, I believe in Finland. Obama's fire-up song was “Lose Yourself”. I think yours would be “House of pain.” Do you have any calisthenics that can help us with nerves? How do we overcome the anxiety that we may have?

Szuplat: As a speechwriter, I lived in a house of pain. As public speakers, you start to get nervous, sweat, your heart races, and your mouth goes dry. Then, you think about your sweating and your pulse racing and your mouth going dry, which makes it all worse. One of the tips that I learned about, which is backed by research, and I've since applied in my own life, is practice when you're excited. What that means is go out for a run, do a bunch of jumping jacks, pull-ups, sit-ups, whatever, run around your house, get your heart racing, start sweating, and then practice your speech. In other words, you're creating the conditions that you will feel later.

When it happens, inevitably, you will recognize that this is not so scary. This is a normal thing. I've actually practiced in this environment while being scared. It's one of the many tips I share in the book, but I think it's great because you're basically recreating the physical sensation of being nervous. It's the same sensation as being excited. It takes a bit of the pain off.

Potolicchio: Final 10 words that you leave us with?

Szuplat: Leave your audience wanting more. We overspeak. You want people leaving and you want them to feel that you've spoken not just to them, but for them. I would sometimes go into the audience after an Obama speech and mingle with them, and they wouldn't know who I was. I would ask them, “What do you think of that speech that you just heard? Was there a line that you remembered most? What did you like about it?” And they would say, “I just loved the way it made me feel.” “He spoke for me.” “He gave voice to my feelings, my hopes, my optimism.”

As a great speaker, you can channel that.